- Theory

The Unwanted Images Project: Liberation, Women and the Printing Press in Partisan Photography

Gal Kirn, in his new book "The Memory of Liberation: Studies on the People's Liberation Struggle in the (Post-) Yugoslav Context" (University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Arts), dedicates one chapter to photographic material from the Unwanted Images archive, in which he explores the representation of liberation, women, and partisan printing houses...

05/05/2025

Autor: Gal Kirn

This chapter starts by crediting the work of the photographer and theorist Davor Konjikušić, whose book on partisan photography compelled him to explore ways to make partisan photos – entrusted to him during research – accessible for further public use. Unwanted Images is a digital platform that assembles interventions, texts, and most of all very precious and not-so-famous photos that were created during the liberation struggle in Yugoslavia. Compared to partisan graphics and poems, partisan photography has received far less attention in art history, and has often been categorized under the genre of war ‘documents’, war-partisan reportage/journalism (for critical take on this view, see Kirn, 2020). In this regard, Davor Konjikušić’s ongoing work (Konjikušić, 2020) and the project called Unwanted Images is a unique online site that not only provides more access and visibility to Yugoslav partisan photography, but also offers a view on a strong political aesthetics to which multiple photos attest. Some may see this project as an updated and more visually focused archival attempt to that of znači.net, but I believe that Unwanted Images as a project raises a number of serious epistemic questions: not only to what, how, and why are we returning, but also whether such a treatment of the emancipatory past offers a way to imagine and create a different future? How can partisan, unwanted photographic material be staged, framed, exhibited and, most importantly, reused and ‘remediated’ in emancipatory ways? The project Unwanted Imagesas a partisan photo-counter-archive does not shy away from the fact that partisan photography took a committed stance, so that its use today will also necessarily entail intervening into the field of memory culture, which is riddled with antagonisms, exclusions, amnesia and blind spots.

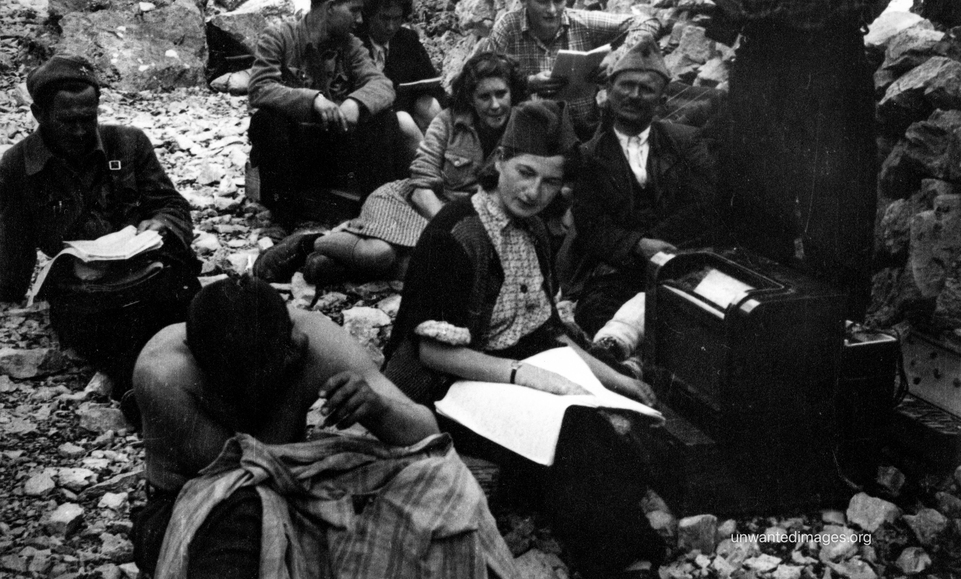

PF-P-002-188, Room of Cultural Workers, Author: Mladen Iveković, 1944.

Furthermore, returning yet again seriously to Karl Marx’s famous 11th thesis on Feuerbach (“Philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it.” MECW 5, 1975, 8), we need to argue that partisan photography should not only capture and represent the world, but inquire into how and in what ways photography can contribute to changing it. Azoulay’s meticulous work on archives and long history of imperialism calls on critical scholarship to unlearn our imperial way of seeing and reading the past (see Azoulay, 2019). One such way to unlearn what remains of imperial and national archives is to launch an antifascist and anti-imperial desire for justice that defragments, rereads, and looks anew at the same material. Can we see the partisans as antifascist, and anti-imperial discontinuity, and contingency that shatters with the imperial photo-camera, ways of reception? Perhaps we could say that partisan photography succeeds not by making certain images ‘eternal’, but rather by capturing ‘contingency’ (Doane, 2002). Partisan ‘photo-eye’ photography captured the fleeting moments of the partisan rupture and revolutionary time, which was constantly ‘deterritorializing’, and its ever-changing territory/space. In this respect, I have selected photos that show the various ways in which partisan men and women organized their struggle and ways of life, imagined new symbolic networks of resistance, and not only captured them in their military actions/fights and photographic poses. In search of images of liberation, it was these multiple angles and partisan ‘photo-eyes’ that managed to capture the processes of liberation that moved men, women, and animals which already constructed an alternative society, and promoted an alternative world for all.

This chapter will select from among those partisan photos that relate to the presentation of women and their multiple activities, on the one hand, and infrastructure of the printing press, on the other. Both women as pivotal subjects and the printing press as a fundamental infrastructure can be thought as crucial for the development and social life of the whole liberation struggle. Before I engage in a close analysis of the selected material, I would like to make a few more points of a general and historical nature about the role and modality of partisan photography.

Partisan Photography: Propaganda, Documentation, and the Ethnography of Resistance

The partisan photography in question was created in wartime, more precisely in the context of the fascist occupation of Yugoslavia. It is also important to note that, at least initially, the PLS political leadership had reservations about the use of photographic cameras. Photography was seen as a weapon that made the party’s movement more vulnerable by exposing its members. Photography could capture and betray the identity of specific partisans, of their secret locations. Even if an individual was not directly threatened, his or her family and close friends could be taken hostage, sent to the camps or shot by the fascist regime. However, a year after the occupation, the General Command of the PLS realized the importance of archiving the resistance in order to document it to the Allies, and also to use it for the future. The well-known Jewish communist intellectual and partisan Moše Pijade, a member of the Liberation Struggle Command, signed the first decree on the partisan archive on 20 October, 1942, which called on the partisan units to collect:

a) one copy of each publication (a newspaper, booklet, leaflet, or any other cultural or other material) and also all future publications […]

b) one copy – of all photographs of our struggles and from behind the front, also the confiscated enemy’s photographs […] each photo needs to state who or what it represents, when and where it was taken, and from whom this photo was taken […].

Quoted in Kurs (Miletić and Radovanović, 2016, 106).

As the war progressed, the partisan resistance became larger and more organized. Photography was assigned an important propaganda role and featured strongly in various propaganda sections of partisan detachments.

From 1943 until the end of the war, the considerable amounts of photographs produced came to number in the tens of thousands and were collected for years after the liberation (mostly by Museums of Revolution in the various cities of socialist Yugoslavia). The photographic archive of the partisans is immense, and covers multiple themes: photos of fascist violence, traces of the fascist occupation, horrific images of dead bodies and animals, burned and abandoned villages, the effects of bombs and weapons on survivors. Another important part of the photo-archive is the documentation of the partisan commandos of everything from their military actions and training to their posing for the camera and doing various vignettes at the partisans’ political and cultural events; finally, the partisan camera also captures contingent moments of the partisans’ everyday life in the liberated areas. Much of this material can be classified under the conventional genre of war photography, the primary function of which, in this instance, was to document the war and the resistance against the fascists during WWII. Many researchers emphasize that partisan photography and partisan art are generally reduced to a propagandistic or, at best, documentary function (Brenk, 1979).

However, this does not preclude looking at partisan art and photography beyond the lens of the ‘documentary-propagandist’. As Komelj’s recent study of partisan art has rightly shown, one must imagine that, for there to be any liberation at all, an immense effort of political will and creativity was invested in cultural activities. And secondly, how can we grasp the impressive quality and abundance of the poems, songs (which measured in tens of thousands), sculptures, drawings, graphics (measured in thousands), photographs and even films that were produced during the war (Komelj, 2008)? Partisan art, and partisan photography, were central neuralgic points that radiated the symbolic power of partisan resistance. With the help of complex partisan print infrastructures this symbolic resistance gained power and contributed to the imaginary of a New World, a new Yugoslavia (Kirn, 2020). The PLS was not only an anti-fascist resistance, but a revolutionary struggle that profoundly changed the social relations and politically oppressive system of the prewar Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

Sanja Horvatinčić points out that from 1943 onwards we can trace a ‘method of reportage documentation’, and that, more importantly, partisan photography contributed to the redefinition of the photographic medium itself, its historical and political scope, making it an inseparable part of the cultural partisan production that engaged in social transformation. Individuals who stood behind the lenses participated themselves in the transformative socio-political process. (Horvatinčić, 2019, 11)

Davor Konjikušić states that the main characteristic of photography was its popular and vernacular practice: “The main actors of partisan art were cultural workers, amateurs, but also authors who had no specific professional and craft knowledge, which thus led to a democratization of the cultural field” (Konjikušić, 2019, 18). This transgression or even abolition of the boundary between authors and producers recalls Walter Benjamin’s hope for an emancipated/communist art that criticizes the established elitist-bourgeois conception of the autonomy of art with its presupposed canon and audience (on the artist-producer, see Benjamin, 1999). Partisan photography, along with other artistic practices, invented new institutions, its own partisan canon, and its own way of doing, producing and disseminating things. Each engaged a photographic camera that produces images for its emerging (counter-) audience is part of a process that Jacques Rancière calls the “emancipated spectator” (Rancière, 2009). Partisan photography helped train the eye for an emergent mode of perception. One of the most famous partisan artists, Božidar Jakac, presented a lecture at the first congress of cultural workers of the Liberation Front in Semič on 4 January 1944: When today, actually on a daily basis, our eyes see a fleeting film of thousands of images and experiences all full of precious and valuable memories, everything is dependent on our experiencing and conceiving of all those moments; what kind of creation of these visible forms should be unfolded, what shall our ancestors see, how can a deeper image of our era be preserved in juxtaposition to the daily reportage that is only an interpreter of events and cannot give us deeper and more permanent experiences? (quoted in Komelj, 2008, 124, translation mine – G.K.)

This is the lesson that Konjikušić’s study of partisan photography confirms. For Konjikušić, photography had not only propagandistic value, but also artistic, documentary and photojournalist value: (Photography) becomes first and foremost the semantic carrier of the message about building a new world and the material for the agitation of the broad masses in building that world. From the beginning, it balanced between the free author approach of partisan photographers and the later attempt to become part of a comprehensive information and propaganda system.

(Konjikušić, 2019, 21, translation mine – G.K.)

As the selected examples in the following subsections demonstrate, photographs in partisan Yugoslavia not only helped to propagate the need for anti-fascist resistance and to mobilize people for the struggle; they documented a wide range of the horrors of fascism and the everyday life of the partisan resistance. In some cases, Konjikušić’s archive even managed to capture the contingency of the emergence of partisan subjectivity and the revolutionary process. Along with some graphic works and drawings, the strongest partisan figures are no longer male partisan heroes, but female figures and the figure of liberation itself. The selected material can be read as a small montage of images that aim to capture the ephemeral, even contingent character, and moments of the partisan transformation.

Concrete Case Studies: Towards a New Figure of Woman

Here I limit myself mostly to those works that aroused a new politico-aesthetical sensibility and were important for the topics at issue, that is, a new female subjectivity. If, in the postwar arts, the dominant partisan figure quickly became a heroic male fighter, a figure replete with weapons and a fearless spirit, a martyr or a victor, then there was more ambivalence around the representation of women. Women were often portrayed as nurses, auxiliary staff, as mourning mothers, and far less often as active fighters (Vittorelli, 2015). Only recently has this representation and narrative about women begun to change, if only gradually, in research and art projects on the AFŽ (see chapter 8, where I detail various researchers and artists).

Let us start with the visual capturing of women as partisan fighters and martyrs. One such example is Lepa Svetozara Radić, a seventeen-year-old partisan fighter who was in charge of caring for the wounded during the Fourth Offensive launched against the partisan forces in central Bosnia. She was part of a group of wounded fighters and fought up to the last hail of bullets, after being besieged by the Prince Eugen division. Severely tortured, she nonetheless refused to reveal the names of the partisan leadership and was publicly executed. The photo shows her strong, calm resilience, which was larger than life itself and reflected the profound resistance that pervaded the partisan struggle.

However, apart from the fact that many women were also fighters in the PLS, I am interested in the images that documented and formed a new figure of the partisan woman, a new collective of emancipated women who organized the AFŽ, which was endowed with its own infrastructure and had a membership of about 2 million women by the war’s end (Dugandžić and Okić, 2017). The partisan struggle cannot be understood apart from the profound process of female emancipation (Kovačević, 1977), which led to a new relationship between (partisan) women and men in the new, partisan Yugoslavia. Concerning the partisans, is there such a thing as a feminine figure of multiplicity? To provide a more visually satisfying answer than that of an individualized female fighter, I propose to interweave various female figures who operated in very different partisan situations: from partisan reproduction and discussions about what to cook for meals, to partisan education, making political speeches and printing; from combat and nursing to arranging the odd leisure activity.

These images express equality and respect between the different roles, positions and activities in the liberation struggle. All of these latter were pivotal for political, cultural and military infrastructure, in short for partisan social reproduction. From this awareness, a stark contrast emerges with the cultural cementing of women as mothers in prewar times, and, to some extent also, to postwar culture. The fact that women could occupy all positions in the liberation struggle, from organizers and fighters to political educators and commissars, that they could vote and be voted for in the political bodies of people power – all this proves that the principle of political equality was deeply rooted in the people’s liberation struggle. This intertwining of women partisans and their multifaceted activities serves as a condensation and reminder of the partisan figure of the women’s collective.

PF-SCN -001-32, A partisan woman reading to comrades.

The constant tension between liberating territories, imagining a new world and the cruel reality of losing fighters, of reprisals that killed civilians, and an awareness of the risk of defeat at the hands of the fascist occupier and collaborationists, who outnumbered the partisans, points to what Benjamin famously calls a “moment of danger”. Evidently images of fights and suffering bring out an awareness of life’s precarity in times of war, but have there been any other images that inscribe this tension between the partisan awareness of annihilation and the expectation of a new world? Is there some image that stands for partisan contingency? For this purpose, I have selected two photographs that express a tense and highly divergent representation of partisan liberation. On the one hand, we see a liberated landscape/village – reminiscent of Breughel’s depiction of a village in a winter landscape. Image 22 shows an emptied landscape with a lone partisan standing as a guard, while Image 23 shows the liveliness of a political-cultural meeting of predominantly peasant women in a liberated forest.

There is no single photograph that succeeded in singularizing a partisan subjectivity from which the entire partisan liberation can be extracted. Rather, it is possible to discern the form and content of a general tendency to inscribe the liberation process in the representation of the partisan movement itself.

PF-N-016-04, On the way from Livno to Starigrad on the island of Hvar. In the photograph from left to right: Slavica Cvrlje Kukoč, Ružica Primorac, and Jure Ruljančić. Photographed in Podgora, October 1943.

Partisan Printing: Real Infrastructure and the Symbolic Network of Empowerment

The last series of photographs brings us to the topic of partisan printing. Yugoslav partisan printing was indisputably one of the most creative and fascinating episodes in all of resistance printing during WWII. The extreme care and dedication shown by the partisans concerning the materials, infrastructure and production of partisan prints point to their political and symbolic importance for the partisan struggle (Repe, 2004). Branko Petranović’s study of partisan printing during the war concludes that more than “3,500 partisan newspapers” were printed during the four years of resistance, as well as “151 poetry collections, 111 books and pamphlets/art prose booklets, and 102 collections of reports” (Petranović, 1988, 371, translation mine – G.K.).

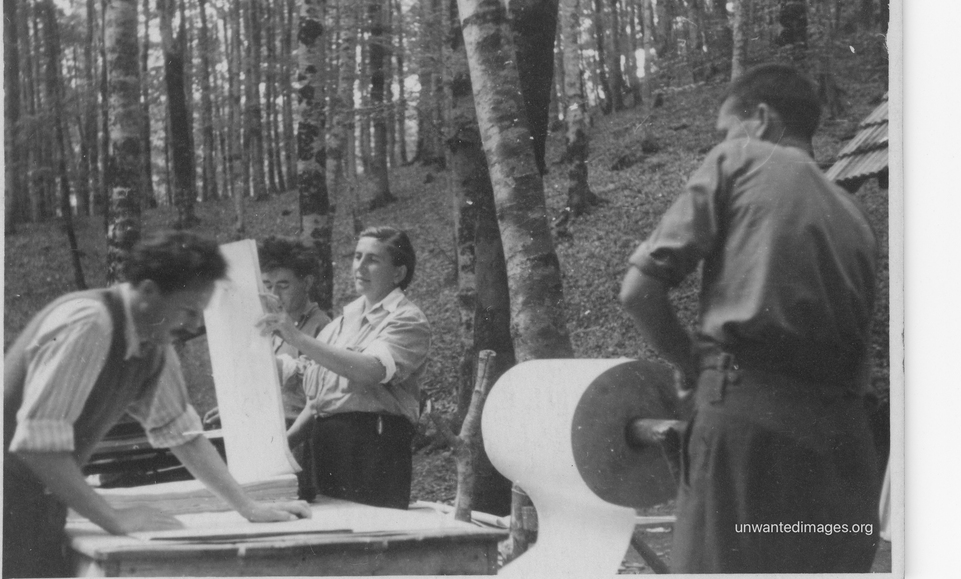

While reviewing photographs of partisan printing activities, one is (visually) struck by the complexity involved in organizing a well-functioning printing machine. Through some valuable photo snippets, we can highlight the inventiveness of the partisan printing process from production and infrastructure to distribution and various uses. The publications were not only periodicals or pamphlets of the Communist Party, but also the printing of posters, poetry collections, the printing of materials for the exhibition of partisan photographs, which enabled the work of reading groups and cultural campaigns. Let us start with the printing material itself. As there was little material for printing, partisan technicians needed to use linoleum they had scraped from the floors, while other materials were confiscated, or smuggled from other occupied urban areas.

The next step involved preparing the paper and the upkeep of the printing machines, which ran almost continuously, spewing forth letters and drawings on paper.

PF-P-005-16, Preparation of paper for print, Mračaj, Petrova Gora, Petar Stanić and Ante Rocca, photo by Žganjer.

In the war’s early stages, the illegal networks in the major cities were of great importance, and members of the resistance developed considerable underground infrastructures and many activities. However, by mid-1942 at the latest, the cultural infrastructure and the majority of the partisan activists had shifted from the cities to the countryside. This shift had to do both with the fascist dismantling of partisan networks, and with the expansion of the liberated territories, and with the establishment of a political and cultural infrastructure in the countryside. This infrastructure included print shops, cultural houses, open-air theatres, photo studios and more. In retrospect, we can consider the print shops as the core of cultural production and dissemination. It was partisan printed matter that formed the symbolic core of the imaginary, disseminating counter-intelligence, poetry, graphics and more. Despite the gradual improvement in infrastructural conditions in early 1943, partisan print shops had to be extremely inventive/rational in their use of materials and infrastructure. Some developed mobile units that printed outdoors in the forest, others printed underground in residential buildings.

It is also noteworthy that the political authority of the resistance was aware that the symbolic struggle and the communicative strategy with people and the allies was crucial for the liberation struggle. For this reason, a lot of energy was invested in building a network of partisan printing houses throughout Yugoslavia. A well-functioning print shop required a dedicated group of editors and scribes, a team of technicians and designers to collect and prepare the material and take care of the machines, and a group of couriers to re-source and distribute the material. Image 30 shows a larger printing house in Lika that counted about 30 members.

Another important visual feature of the partisan space is its multifunctionality following the maxim ‘less is more’. The partisans’ capacity for innovation can be seen here in their ability to create a space that would serve as a kitchen, a print shop, and a small warehouse.

Finally, the printing activities that related to educational campaigns were crucial not only for mobilizing partisans, but also for changing social relations. In the prewar period, rural areas were seen as bastions of provincialism and illiteracy (about 80% of the Yugoslav population were illiterate peasants), and traditionally it was also the church (whether Catholic, Orthodox, Islamic, or Jewish) that organized the local community and most often promulgated a conservative, anti-communist ideology, since Bolshevik ideology was portrayed as supposedly anti-moral (they steal and corrupt your women) and anti-property (they steal your land). Therefore, the peasantry was always seen as a conservative force, also by many communist leftists. However, during the partisan liberation struggle, the peasantry and the countryside in general became increasingly politicized, which also changed the main social base of the revolutionary subject. Most of the partisan struggles occurred here as did the organization of political and cultural life by the people. In many reading seminars, illiterate people were taught how to read, and also how to write their own notes and poems. Fight during the day, write poems at night, very much reminiscent of the proletarian archives that Jacques Rancière traced (2012). Similar to the way that workers rejected what was expected from them, and also denied the typical divisions of labour requiring them to sleep at night, they used the nights to educate themselves, to read and write, to emancipate themselves at night. Here, the figure of peasant breaks with the image of a backward rural, patriarchal idiot and becomes part of a subjectivity of ‘partisan-poets’ that is fully emancipated.

As Miklavž Komelj (2008, 58–59) rightly notes, the Yugoslav countryside was more progressive than the urban centres until the end of the war. People’s collective emancipation, their capacity to break with the dominant expectation to subjugate, and collaborate, and rather be able to imagine an alternative world, to engage in mutual aid and support, as well as to fight successfully against the Nazi army, all this turned the tables in favour of the countryside. Also importantly, the struggle and practice of printing led to experimentation among partisan artists and technicians, who reinvented printing techniques and obtained elementary materials in the most impossible circumstances, scraping the floors of houses and workshops (as linoleum and wood were often used).

Finally, I would like to mention that partisan printed matter not only circulated by hand, but – in addition to graphics, photography, posters – was exhibited in partisan exhibitions and also in mobile photo exhibitions/on wallpapers. Such partisan photo exhibitions are relatively well-known aspects of the history of partisan photography (Konjikušić, 2019); they were put on in the liberated territories and their cultural spaces throughout all Yugoslavia.

The dissemination format of mobile and short-term photo exhibitions, an area that is still little studied, is valuable because its form demonstrates the deterritorializing nature of partisan dissemination. Fabec and Vončina were the first to study this format, explaining that “mobile exhibitions consisted of 20 to 40 photographs, mostly in 18 × 24 cm format [...] and were placed in visible places in villages and in town squares” (Fabec and Vončina, 2005, 115, translation mine – G.K.). These photographs could be seen by villagers, townspeople and partisan troops, but also by enemies – they could be seen by anyone in the area. In a way, this gesture put valuable material on display and showed not only the presence of partisan resistance, but also of partisan art. Speaking only of the level of dissemination and the specific form of partisan art, one could say that the most appropriate cultural forms and formats of partisan art were undoubtedly found in the travelling photo exhibitions and the mobile theatre groups that journeyed throughout the liberated territories. The mobile theatre groups were particularly successful in moving people and contributing to new partisan performances and to the dissemination of works and practices. While the organization and processing of photographic material produced cinematic effects on the audience, these mobile photo exhibitions pointed to an invention – experimenting with the mobile format of the exhibition, the photos were sent on the road with the partisans.

PF-P-002-334, Women, peasants and youth on the politico-cultural meeting, fond of Mladen Iveković.

Conclusion

This chapter attempted to defragment the partisan (photographic) history of the Yugoslav PLS by paying particular attention to the creation of a new figure of the (partisan) woman and the centrality of partisan print in the creation of a New World. The examples examined here were collected as part of an ongoing study on the partisan image and they attest to the profound self-reflexivity that Yugoslav partisans displayed during the struggle for liberation. I have shown that cultural activities were central to understanding the construction of international solidarity and the imaginary of the New World (the new Yugoslavia), and that it was possible to practise a high level of formal experimentation. The visual history of the oppressed and especially of women’s emancipation was overshadowed by the promotion of masculine heroics, as seen in partisan film under socialism right up to the even more misogynistic character of nationalist revisionism in the 1990s. The partisan visual counter-archive can help us mobilize emancipatory material from the past by pointing to the creative combination of intermedial art forms and comradely collaboration between artists, cultural workers and amateurs. The selected images are not a closed selection. Instead, they form a starting point for future research, for creating a space in which solidarity among the oppressed is (re)established, even if they are distant to each other in time and space.

Full book in PDF is available on this link: https://shorturl.at/hLsUh

Bibliography:

Azoulay, A.A., 2019: Potential History. Unlearning Imperialism. London: Verso.

Brenk, F., 1979: O filmski in fotografski kulturi med narodnoosvobodilnim bojem. In: Kultura, revolucija in današnji čas (ed. Franček Bohanc), Ljubljana, 61–67.

Doane, M. A., 2002: The Emergence of Cinematic Time: Modernity, Contingency, the Archive, Cambridge.

Dugandžić, A., and Okić, T., 2016: Izgubljena Revolucija: AFŽ Između Mita i Zaborava. Sarajevo: Udruženje za kulturu i umjetnost Crvena.

Fabec, F., and Vončina, D., 2005: Slovenska odporniška fotografija. Ljubljana.

Kirn, G., 2020: The Partisan Counter-Archive. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Komelj, M., 2008: Kako Misliti Partizansko Umetnost? Ljubljana: Založba cf/*.

Konjikušić, D., 2019: Red Light - Yugoslav Partisan Photography and Social Movement 1941–1945. Belgrade: Rosa Luxemburg Foundation.

Marx, K., 1845 [1975]: Theses on Feuerbach. In: Marx, K. and Engels, F. (eds)

Marx/Engels Collected Works, vol. 5. Moscow: Progress Publishers, p. 8.

Marx, K., 1867 [1967]: Capital, vol. 1. New York: Vintage.

Petranović, B., 1988: Istorija Jugoslavije II: Narodnooslobodilački Rat i Revolucija. Beograd: Nolit.

Radanović, M., 2016: Kazna i Zločin: Snage Kolaboracije u Srbiji. Belgrade: Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung.

Rancière, J., 2012: Proletarian Nights: The Workers’ Dreams in the Nineteenth-Century France. Verso: London.

Vittorelli, N., 2015: With or without gun: staging female partisans in socialist Yugoslavia. In: Partisans in Yugoslavia: Literature, Film and Visual Culture. (eds Jakiša, Miran).